A Call to Action – Local Housing Market Rewards, Risks, and Levers for Stability

This morning, I was reading a Kellog article on rockets and feathers. If you’re not familiar with the reference, “rocket and feather” is an economic term that describes how prices rise like a rocket and fall like a feather. As I think about recent local housing news, and the increase in housing prices since the pandemic, I can help but see those increases through the “rocket” term. Prices of materials skyrocketed as did rents and sale prices. Other production costs beyond materials like insurance, utilities, and labor also rose at various levels. And, while I can see, based on past experiences and historic trends, materials, insurance, and other costs will come down in a feather-like analogy, I worry, especially in northern Illinois the sales price down slide will be less like a feather and more like crash.

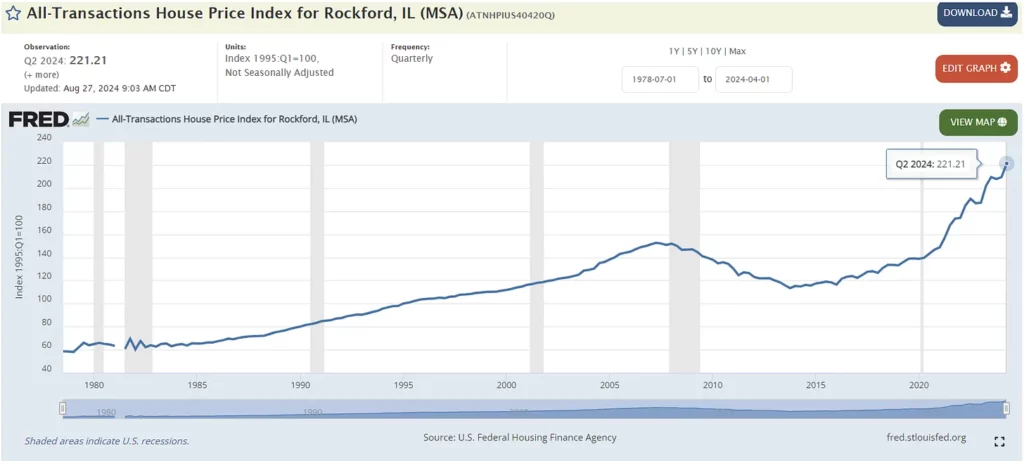

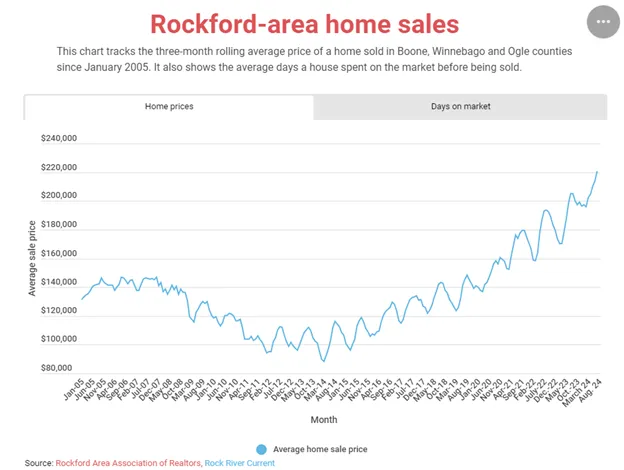

If you hadn’t seen last week’s sales price release by the NorthWest Illinois Alliance of Realtors, July prices beat June home sale prices, a condition that has been several months (49) running; however, this was more than a consecutive price increase, it is the second month in 2024 we topped record high prices. The three-month rolling average price of a home sold in Winnebago, Boone and Ogle counties was $213,644 in June, breaking the May record of $210,089. June 2024 average price is up approximately 8% from June 2023, when average prices reached what was then a record high of $198,254. Last month we were the third hottest market in the nation according to a new report by Realtor.com. This is great for sellers harvesting gains from historically low purchase prices and low interest rates; however, is this healthy for long-term market gains and sustainability? Historically, what happens when housing prices continues to rise and there is no new inventory introduced into the market to address supply – one of the biggest drives of price appreciation? Historically, we see a crash. Our region can’t afford a crash.

Today I will examine the economic and social consequences of a housing market characterized by persistently low inventory and rising home prices. We’ll explore the factors contributing to limited housing inventory, the resulting upward pressure on home prices, and the effects on buyers, sellers, and the broader economy. Through an analysis of historical trends, current market dynamic, and economic theory, I’ll give thought to both short-term and long-term implications for affordability, homeownership rates, and wealth inequality. I will also address possible policy solutions at the local, state, and federal levels.

Our housing market plays a critical role in shaping the economic health of our residents and our region. Housing is not only a basic need but also a primary means of wealth accumulation. When housing inventory is low and prices continue to rise, market dynamics shift, creating ripple effects throughout the economy. Let’s explores what happens when a housing market faces a persistent shortage of homes, driving prices upward and impacting various stakeholders.

First, why do we see scarcity in current housing inventory? There are several factors that affect both supply and demand.

Supply-side drivers:

– A reduction in new housing developments due to high construction costs, labor shortages, and zoning restrictions severely limit housing supply. This has been our largest supply constraint for the past decade plus.

– Aging housing stock that has fallen into disrepair and beyond reasonable repair, blight, and demolition removes units from the market. This is a regional condition most prevalent in the city of Rockford.

– Homeowners staying put due to low-interest mortgages or the difficulty of finding a new home creates a logjam, further restricting the supply of homes for sale.

Demand-side drivers:

– Population and job growth demand without a corresponding increase in supply.

– The influx of investors can further exacerbate the shortage, especially in metropolitan markets like Rockford.

– Shifts in demographics, such as millennials entering peak homebuying age or retirees downsizing, may put additional pressure on available inventory.

Rising home prices:

When housing inventory is low, competition among buyers increases, driving up home prices. In a market with rising prices, several events occur:

– With multiple buyers vying for a limited number of homes, sellers are often able to push prices higher as buyers engage in bidding wars, offering more than the asking price. We’ve seen this.

– Rising prices lead to home price appreciation, benefiting current homeowners but locking out potential first-time buyers, as homeownership becomes increasingly unattainable. We’ve seen this.

– Investors, seeing prices continue to climb, may enter the market, further inflating demand. This can create speculative bubbles, where homes are purchased not for living but as a rental investment. We’ve seen this.

Impact on buyers and sellers:

- Affordability Crisis: As home prices rise, many potential buyers, especially first-time buyers, find themselves priced out of the market. We’ve seen this reported in the media. The affordability crisis worsens as wages fail to keep pace with skyrocketing home values. Buyers may have to stretch their finances, increasing debt-to-income ratios and reducing financial flexibility. Many are forced to rent, leading to higher demand in the rental market and rising rents.

We’ve seen this. In our region, unlike many cooling markets across the nation, we have record high rents because there is also a deficit of units on the supply-side having been little production here too. This condition is incredibly problematic for our region as we foresee significant job growth over the next three years and few housing units to meet this demand.

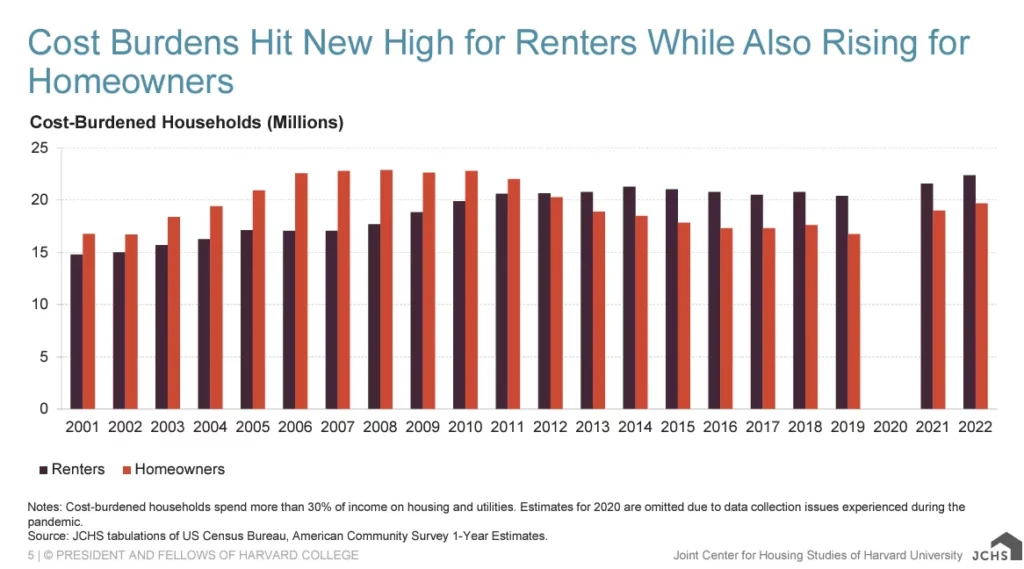

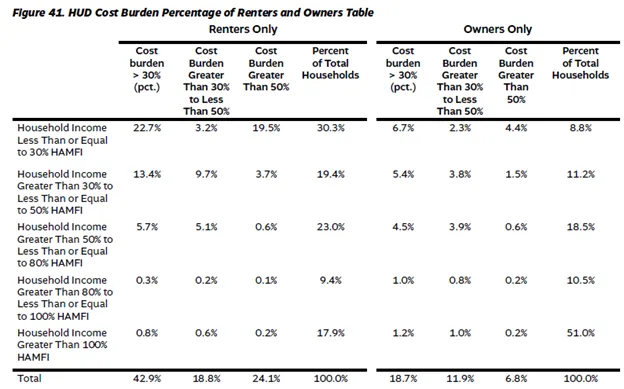

Proving up this affordability crisis, locally we are seeing low vacancy rates and significant “housing burden” rates, or the number of residents who pay more than 30% of their income to housing costs, rent or mortgage payments and utility costs. In the chart below we see rental burden rates just under twenty-five percent (1 in 4 renters), and just under twenty percent for homeowners (1 in 5 homeowners). Locally, we see the highest burden rates in the city of Rockford at nearly forty-three percent for renters and nearly 19% for homeowners, as reported by the city in its Housing Needs Assessment and Market Study 2023-2032. Other data sources place current burden rates near sixty percent and twenty-eight respectively.

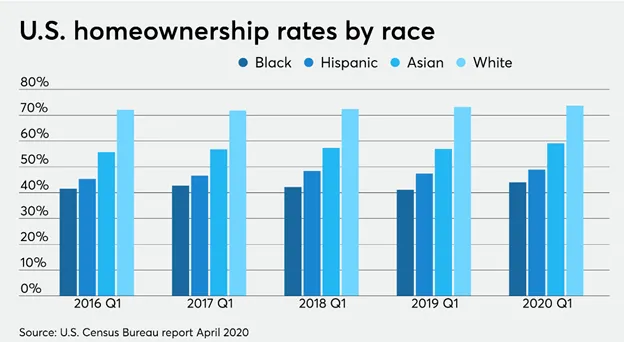

– Wealth Inequality: The widening gap between those who own homes and those who do not leads to increased wealth inequality. Homeowners benefit from rising property values, while non-owners struggle with high housing costs and limited ability to save for future home purchases. Additionally, there are strong disparities in wealth for minorities over whites leading to added community inequality.

– Impact on Sellers: While sellers benefit from higher home prices, they also face challenges. Many homeowners hesitate to sell because they fear they will not be able to find a new home in the tight market. This “lock-in” effect further reduces housing inventory, exacerbating the shortage.

Broader economic implications:

– Reduced Mobility: High home prices reduce mobility, as people are less likely to move if they cannot afford a comparable home in another location. This impacts job markets, as workers may be unwilling or unable to relocate for employment opportunities. For me, this is one of our largest risks if we intend to grow population through recent economic investments to spur job growth.

– Slowdown in Economic Growth: A lack of affordable housing can hinder economic growth, as businesses face challenges in attracting and retaining workers. High housing costs also reduce disposable income, limiting consumer spending in other areas like healthcare, transportation, and education.

– Rental Market Pressures: When potential homebuyers are priced out of the market, they turn to renting, increasing demand and driving up rental prices. Rising rents can create financial strain for renters, reducing their ability to save for a future home purchase, further entrenching the divide between homeowners and non-owners. Additionally, we know when households are cost burdened, they spend less on preventative healthcare and other household stabilizing investments.

Policy Solutions and Long-Term Considerations:

Addressing the issue of limited housing inventory and rising prices requires national, state, and local short-term and long-term solutions. Some potential approaches include:

– Increasing Housing Supply: Local policymakers can encourage the construction of more homes by easing zoning regulations, providing incentives for builders, and reducing construction costs. This can help alleviate the supply-demand imbalance over time; however, locally we have seen little progress in making the significant changes necessary to stimulate supply.

– Affordable Housing Initiatives: Governments (local, state, and Federal) can promote affordable housing by subsidizing the construction of low- and middle-income housing, offering down payment assistance to first-time buyers, or implementing rent control measures in areas with rapidly rising rents.

– Interest Rate Adjustments: Central banks (federal) can manage rising housing prices by adjusting interest rates. Higher interest rates can reduce demand by making mortgages more expensive, though this may have broader economic consequences as we’ve seen recently.

– Tax Reforms: (Local, state, federal) Implementing or adjusting property taxes, capital gains taxes, or other fiscal measures may curb speculative behavior in the housing market, discouraging investors from driving up prices in the absence of increased demand for housing as a residence.

Final thoughts:

The combination of limited housing inventory and rising home prices has far-reaching consequences for both individuals and the economy. While existing homeowners benefit from appreciating property values, the affordability crisis exacerbates wealth inequality and restricts opportunities for potential buyers and business. Addressing this issue requires a coordinated policy response aimed at increasing housing supply, supporting first-time buyers, and ensuring that the housing market remains accessible and sustainable for all. Without intervention, the long-term impacts of high housing prices may continue to distort the market, reduce mobility, and worsen economic inequality.

Options to increase housing production are really the levers we need to pull to ensure stability in our market. Assuming materials and other costs stabilize and float downward in that feather analogy, our levers are predominantly policy driven.

Federal policies – Last weeks presidential debate elevated the housing affordability crisis. “We have never seen that before in a presidential debate between two major candidates, and certainly we’re hearing about housing affordability in elections at all levels, federal, state and local, far more than we have previously,” says Diane Yentel, President and CEO of the National Low Income Housing Coalition. “It’s a reflection both of how severe the housing affordability crisis has become and also of the organizing that’s putting pressure on politicians to respond.”

Since the real log jams are production costs and local zoning, it is likely the federal levers will be subsidies that spur reductions in the costs to build, finance, and buy or rent housing. These may look like ancillary cost reduction incentives, lowered interest rates, buyer subsidies, and housing rental vouchers. While all have their own implementation challenges, we should be seeking a candidate who will seek to influence the market in a broader way than simply throwing money at it.

At the state level, we see policies and priorities taking several different approaches. Most options include similar investments and subsidies that buy down the cost of production vs. incentivize housing production for direct investments or inventory growth that also produce tax revenue growth. Some states provide tax credits to investors, developer, and/or builders who invest in production that drive that tax revenue. Not all states do. Others have taken a broad approach to overcome local zoning challenges by passing state legislation that overrides local zoning codes to spur production. It seems the latter produces significant political disagreement and challenge.

Locally, across Illinois communities I see almost every community acknowledging the housing crisis but few making meaningful change in land use policies and building permitting processes that will help reduce costs or spur production by compounding on other policy actions at state and federal levels. Some cities, like Minneapolis, have taken bold actions toward solving their affordability crisis and building inventory.

Minneapolis became a national leader in land use reform when it passed the Minneapolis 2040 Plan in 2018. One of the plan’s most significant and controversial changes was the elimination of single-family zoning throughout the city. Under this new policy, up to three units of housing—duplexes or triplexes—are allowed on any residential lot that was previously zoned for single-family homes. This reform was motivated by the need to address racial and economic disparities, housing shortages, and climate resilience.

Minneapolis’ zoning reform aimed to increase the housing supply and offer more affordable options. Early indicators suggest that the policy is beginning to increase the number of small-scale multifamily developments in neighborhoods previously limited to single-family homes. Additionally, the city’s approach has sparked nationwide discussions about the need for zoning reform to promote housing equity.

The reform faced significant opposition from residents concerned about neighborhood character, property values, and parking. Despite these concerns, the Minneapolis 2040 Plan represents a bold step toward addressing housing shortages and making the city more affordable for its workforce and more equitable for its minority residents.

Can this work in a place like Rockford, or its surrounding communities? It has worked for more than a century. I live in Edgewater, a historic neighborhood, that falls among our city’s most desirable neighborhoods. With homes, duplexes, four-families, and many apartment communities, on the ground for decades, the neighborhood has not seen lower property values or parking challenges because of this. Concerns about neighborhood character do not exist because this diversity of housing types and residents is our neighborhood’s character and something that attracts residents over the homogeneity in new single family only neighborhoods.

A Case for Voter Action:

With all of this information and so many different levels at which influence happens, what can you do about our housing crisis? Vote for candidates who have housing plans and fact-based platforms to change the decline of our housing stock and neighborhoods, the lack of production, and the unsustainable rising costs. Vote for candidates who are working, or promise to work, with their peers to draft meaning housing plans that build on improved land use policies. If our elected officials do not have such plans or policy ideas, demand they do or don’t vote for them. This housing crisis has been mounting for many years and for too many years we, as citizens have allowed it. Stop allowing inaction to be our plan and demand housing policies and written plans with measurable goals. Successful communities have them. We should too.